7 Happiness Sins a Life of Happiness and Fulfillment Review

The philosophy of happiness is the philosophical concern with the existence, nature, and attainment of happiness. Some philosophers believe happiness can exist understood as the moral goal of life or as an aspect of chance; indeed, in about European languages the term happiness is synonymous with luck.[1] Thus, philosophers commonly explicate on happiness as either a state of mind, or a life that goes well for the person leading it.[2] Given the businesslike business organization for the attainment of happiness, research in psychology has guided many mod day philosophers in developing their theories.[3]

Ancient Greece [edit]

Democritus [edit]

Democritus (c. 460 – c. 370 BC) is known as the 'laughing philosopher' because of his emphasis on the value of 'cheerfulness'.[4]

Plato [edit]

We have proved that justice in itself is the all-time thing for the soul itself, and that the soul ought to practice justice...

Plato (c. 428 – c. 347 BCE), using Socrates (c. 470 – 399 BCE) as the main character in his philosophical dialogues, outlined the requirements for happiness in The Republic.

In The Republic, Plato asserts that those who are moral are the just ones who may be truly happy. Thus, one must understand the key virtues, particularly justice. Through the thought experiment of the Band of Gyges, Plato comes to the conclusion that one who abuses ability enslaves himself to his appetites, while the man who chooses non to remains rationally in control of himself, and therefore is happy.[five] [6]

He also sees a blazon of happiness stemming from social justice through fulfilling one's social function; since this duty forms happiness, other typically seen sources of happiness – such as leisure, wealth, and pleasure – are deemed lesser, if non completely imitation, forms of happiness.[7]

Aristotle [edit]

Aristotle (384 – 322 BCE) was considered an ancient Greek scholar in the disciplines of ethics, metaphysics, biology and phytology, amid others.[eight] Aristotle described eudaimonia (Greek: εὐδαιμονία) as the goal of human thought and activeness. Eudaimonia is often translated to hateful happiness, but some scholars argue that "human being flourishing" may be a more accurate translation.[9] More than specifically, eudaimonia (arete, Greek: ἀρετή) refers to an inherently positive and divine state of being in which humanity can actively strive for and achieve. Given that this state is the most positive country for a human to be in, it is often simplified to mean happiness. However, Aristotle's use of the term in Nicomachiean Ideals extends beyond the general sense of happiness.[10]

Within the Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle points to the fact that many aims are actually only intermediate aims, and are desired just because they brand the achievement of higher aims possible.[xi] Therefore, things such as wealth, intelligence, and courage are valued simply in relation to other things, while eudaimonia is the simply affair valuable in isolation.

Aristotle regarded virtue as necessary for a person to be happy and held that without virtue the most that may be attained is contentment. For Aristotle, achieving virtue involves request the question "how should I exist" rather than "what should I do". A fully virtuous person is described every bit achieving eudaimonia, and therefore would be undeniably happy. The acquisition of virtue is the chief consideration for Aristotelian Virtue Ethics.[8] Aristotle has been criticized for failing to evidence that virtue is necessary in the way he claims it to be, and he does not address this moral skepticism.[12]

Cynicism [edit]

Marble statue of Aristotle, created past Romans in 330 BC.

Antisthenes (c. 445 – c. 365 BCE), frequently regarded as the founder of Pessimism, advocated an ascetic life lived in accordance with virtue. Xenophon testifies that Antisthenes had praised the joy that sprang "from out of ane's soul,"[thirteen] and Diogenes Laërtius relates that Antisthenes was addicted of saying: "I would rather go mad than feel pleasure."[14] He maintained that virtue was sufficient in itself to ensure happiness, but needing the strength of a Socrates.

He, along with all following Cynics, rejected any conventional notions of happiness involving money, power, and fame, to lead entirely virtuous, and thus happy, lives.[15] Thus, happiness can exist gained through rigorous grooming (askesis, Greek: ἄσκησις) and by living in a way which was natural for humans, rejecting all conventional desires, preferring a uncomplicated life gratuitous from all possessions.

Diogenes of Sinope (c. 412 – c. 323 BCE) is virtually frequently seen every bit the perfect embodiment of the philosophy. The Stoics themselves saw him as i of the few, if not just, who have had achieved the country of sage.[sixteen]

Cyrenaicism [edit]

Equally a consequence the sage, fifty-fifty if he has his troubles, will nonetheless be happy, even if few pleasures accumulate to him.

The Cyrenaics were a schoolhouse of philosophy established by Aristippus of Cyrene (c. 435 – c. 356 BCE). The school asserted that the only good is positive pleasance, and pain is the just evil. They posit that all feeling is momentary then all past and future pleasure accept no real existence for an individual, and that among nowadays pleasures there is no distinction of kind.[19] Claudius Aelianus, in his Historical Miscellany,[20] writes nearly Aristippus:

"He recommended that one should concrete on the nowadays 24-hour interval, and indeed on the very part of information technology in which one is acting and thinking. For but the present, he said, truly belongs to us, and not what has passed by or what we are anticipating: for the one is gone and done with, and it is uncertain whether the other will come to be"[21]

Some firsthand pleasures can create more than their equivalent of pain. The wise person should be in control of pleasures rather than exist enslaved to them, otherwise hurting will consequence, and this requires sentence to evaluate the unlike pleasures of life.[22]

Pyrrhonism [edit]

Pyrrhonism was founded by Pyrrho (c. 360 – c. 270 BCE), and was the commencement Western schoolhouse of philosophical skepticism. The goal of Pyrrhonist practise is to attain the land of ataraxia (ataraxia, Greek: ἀταραξία) – freedom from perturbation. Pyrrho identified that what prevented people from attaining ataraxia was their behavior in non-evident matters, i.e., belongings dogmas. To costless people from conventionalities the aboriginal Pyrrhonists developed a variety of skeptical arguments.

Epicureanism [edit]

Of all the means which wisdom acquires to ensure happiness throughout the whole of life, by far the most important is friendship.

—Epicurus[23]

Epicureanism was founded past Epicurus (c. 341 – c. 270 BCE). The goal of his philosophy was to attain a state of quiet (ataraxia, Greek: ἀταραξία) and freedom from fear, as well as absence of bodily pain (aponia, Greek: ἀπονία). Toward these ends, Epicurus recommended an austere lifestyle, noble friendship, and the avoidance of politics.

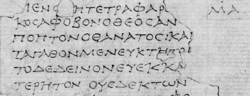

I assist to achieving happiness is the tetrapharmakos or the four-fold cure:

"Exercise not fright god,

Do non worry about decease;

What is good is easy to get, and

What is terrible is easy to endure."

(Philodemus, Herculaneum Papyrus, 1005, four.9–14).[24]

Stoicism [edit]

If y'all work at that which is before you, following right reason seriously, vigorously, calmly, without allowing annihilation else to distract y'all, but keeping your divine role pure, as if you were bound to give information technology back immediately; if y'all hold to this, expecting nil, only satisfied to live now co-ordinate to nature, speaking heroic truth in every discussion that you utter, you volition live happy. And at that place is no man able to preclude this.

Stoicism was a school of philosophy established by Zeno of Citium (c. 334 – c. 262 BCE). While Zeno was syncretic in idea, his primary influence were the Cynics, with Crates of Thebes (c. 365 – c. 285 BCE) every bit his mentor. Stoicism is a philosophy of personal ideals that provides a system of logic and views most the natural earth.[26] Modernistic utilize of the term "stoic" typically refers not to followers of Stoicism, but to individuals who feel indifferent to experiences of the earth, or represses feelings in general.[27] Given Stoicism's accent on feeling indifferent to negativity, it is seen every bit a path to achieving happiness.[28]

Stoics believe that "virtue is sufficient for happiness".[29] One who has attained this sense of virtue would go a sage. In the words of Epictetus, this sage would be "sick and nonetheless happy, in peril and yet happy, dying and yet happy, in exile and happy, in disgrace and happy."[thirty]

The Stoics therefore spent their time trying to attain virtue. This would only be achieved if ane was to dedicate their life studying Stoic logic, Stoic physics, and Stoic ideals. Stoics draw themselves equally "living in understanding with nature." Sure schools of Stoicism refer to Aristotle's concept of eudaimonia every bit the goal of practicing Stoic philosophy.[31]

Ancient Rome [edit]

Schoolhouse of the Sextii [edit]

The School of the Sextii was founded by Quintus Sextius the Elder (fl. 50 BCE). Information technology characterized itself mainly as a philosophical-medical school, blending Pythagorean, Platonic, Cynic, and Stoic elements together.[32] They argued that to reach happiness, one ought to exist vegetarian, have nightly examinations of conscience, and avert both consumerism and politics,[33] and believe that an elusive incorporeal power pervades the body.[32]

Augustine of Hippo [edit]

Yet, to praise you is the desire of man, a piddling piece of your cosmos. Yous stir man to accept pleasure in praising you, because you have made united states for yourself, and our heart is restless until it rests in you.

The happy life is joy based on the truth. This is joy grounded in you, O God, who are the truth.

St. Augustine of Hippo (354 – 430 Advert) was an early Christian theologian and philosopher[36] whose writings influenced the development of Western Christianity and Western philosophy.

For St. Augustine, all human deportment revolve around love, and the primary trouble humans face is the misplacing of dear.[37] Only in God can one notice happiness, equally He is source of happiness. Since humanity was brought along from God, but has since fallen, one's soul dimly remembers the happiness from when one was with God.[38] Thus, if one orients themselves toward the love of God, all other loves volition become properly ordered.[39] In this mode, St. Augustine follows the Neoplatonic tradition in asserting that happiness lays in the contemplation of the purely intelligible realm.[38]

St. Augustine deals with the concept of happiness directly in his treatises De beata vita and Contra Academicos.[38]

Boethius [edit]

Mortal creatures have one overall concern. This they work at by toiling over a whole range of pursuits, advancing on different paths, simply striving to attain the one goal of happiness.

Boethius (c. 480–524 AD) was a philosopher, most famous for writing The Alleviation of Philosophy. The work has been described every bit having had the unmarried near important influence on the Christianity of the Middle Ages and early Renaissance and as the last great work of the Classical Period.[41] [note 1] The book describes many themes, just among them he discusses how happiness can be attainable despite changing fortune, while considering the nature of happiness and God.

He posits that happiness is acquired past attaining the perfect good, and that perfect skillful is God.[40] He so concludes that every bit God ruled the universe through Love, prayer to God and the application of Honey would pb to true happiness.[42]

Centre Ages [edit]

Avicenna [edit]

A drawing of Avicenna, 1960.

Avicenna (c. 980–1037), also known as 'Ibn-Sina', was a polymath and jurist; he is regarded as one of the virtually significant thinkers in the Islamic Aureate Historic period.[43] According to him, happiness is the aim of humans, and that real happiness is pure and free from worldly interest.[44] Ultimately, happiness is reached through the conjunction of the human intellect with the split agile intellect.[45]

Al-Ghazali [edit]

Al-Ghazali (c. 1058–1111) was a Muslim theologian, jurist, philosopher, and mystic of Western farsi descent.[46] Produced near the end of his life, al-Ghazali wrote The Alchemy of Happiness (Kimiya-yi Sa'ādat, (Persian: كيمياى سعادت).[47] In the work, he emphasizes the importance of observing the ritual requirements of Islam, the actions that would atomic number 82 to conservancy, and the abstention of sin. Only by exercising the human faculty of reason – a God-given ability – can i transform the soul from worldliness to complete devotion to God, the ultimate happiness.[48]

Co-ordinate to Al-Ghazali, in that location are four main constituents of happiness: self-cognition, knowledge of God, knowledge of this world every bit it really is, and the knowledge of the adjacent world as it really is.[49]

Maimonides [edit]

Maimonides (c. 1135–1204) was a Jewish philosopher and astronomer,[50] who became one of the well-nigh prolific and influential Torah scholars and physicians.[51] He writes that happiness is ultimately and essentially intellectual.[52]

Thomas Aquinas [edit]

God is happiness by His Essence: for He is happy not by acquisition or participation of something else, simply by His Essence.

St. Thomas Aquinas (1225 – 1274 AD) was a philosopher and theologian, who became a Doctor of the Church building in 1323.[54] His system syncretized Aristotelianism and Cosmic theology within his Summa Theologica.[55] The first part of the second part is divided into 114 manufactures, the get-go five deal explicitly with the happiness of humans.[56] He states that happiness is accomplished by cultivating several intellectual and moral virtues, which enable us to understand the nature of happiness and motivate united states of america to seek it in a reliable and consequent manner.[55] Yet, one will be unable to find the greatest happiness in this life, because terminal happiness consists in a supernatural union with God.[55] [57] As such, man'due south happiness does not consist of wealth, status, pleasance, or in any created proficient at all. Most appurtenances practice not have a necessary connection to happiness,[55] since the ultimate object of human'south will, tin can but be institute in God, who is the source of all expert.[58]

Early on Modernistic [edit]

Michel de Montaigne [edit]

Michel de Montaigne (1533–1592) was a French philosopher. Influenced past Hellenistic philosophy and Christianity, alongside the confidence of the separation of public and private spheres of life, Montaigne writes that happiness is a subjective state of mind and that satisfaction differs from person to person.[59] He continues by acknowledging that i must exist allowed a individual sphere of life to realize those particular attempts of happiness without the interference of society.[59]

Jeremy Bentham [edit]

Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832) was a British philosopher, jurist, and social reformer. He is regarded as the founder of modernistic utilitarianism.

His item brand of utilitarianism indicated that the most moral activeness is that which causes the highest amount of utility, where defined utility as the aggregate pleasure after deducting suffering of all involved in any activeness. Happiness, therefore, is the experience of pleasure and the lack of pain.[sixty] Actions which do not promote the greatest happiness is morally wrong – such as ascetic sacrifice.[60] This manner of thinking permits the possibility of a calculator to mensurate happiness and moral value.

Arthur Schopenhauer [edit]

Arthur Schopenhauer (1788–1860) was a German philosopher. His philosophy express that egotistical acts are those that are guided by self-involvement, desire for pleasure or happiness, whereas but compassion can be a moral human activity.

Schopenhauer explains happiness in terms of a wish that is satisfied, which in turn gives ascent to a new wish. And the absence of satisfaction is suffering, which results in an empty longing. He also links happiness with the movement of time, equally we experience happy when time moves faster and feel sad when fourth dimension slows down.[61]

Contemporary [edit]

Władysław Tatarkiewicz [edit]

Władysław Tatarkiewicz (1886–1980) was a Smoothen philosopher, historian of philosophy, historian of art, esthetician, and ethicist.[62]

For Tatarkiewicz, happiness is a fundamental upstanding category.

Herbert Marcuse [edit]

Herbert Marcuse (1898–1979) was a German language-American philosopher, sociologist, and political theorist, associated with the Frankfurt School of critical theory.

In his 1937 essay 'The Affirmative Character of Civilization,' he suggests culture develops tension inside the structure of order, and in that tension tin challenge the current social order. If it separates itself from the everyday world, the demand for happiness volition cease to be external, and brainstorm to become an object of spiritual contemplation.[63]

In the Ane-Dimensional Human, his criticism of consumerism suggests that the current system is one that claims to exist autonomous, but is disciplinarian in graphic symbol, equally only a few individuals dictate the perceptions of freedom past only assuasive certain choices of happiness to be bachelor for purchase.[64] He further suggests that the conception that 'happiness tin be bought' is one that is psychologically dissentious.

Viktor Frankl [edit]

Information technology is a feature of the American civilisation that, again and again, one is commanded and ordered to 'exist happy.' But happiness cannot be pursued; information technology must ensue. One must have a reason to 'be happy'.

Viktor Frankl (1905–1997) was an Austrian neurologist, psychiatrist, Holocaust survivor and founder of logotherapy. His philosophy revolved effectually the emphasis on meaning, the value of suffering, and responsibility to something greater than the self;[65] only if one encounters those questions tin can ane exist happy.

Robert Nozick [edit]

Robert Nozick (1938–2002) was an American philosopher[66] and professor at Harvard University. He is best known for his political philosophy, but he proposed 2 thought experiments directly tied to issues on Philosophy of Happiness.

In his 1974 book, Anarchy, State, Utopia, he proposed a idea experiment where one is given the choice to enter a auto that would give the maximum amount of unending hedonistic pleasure for the entirety of one's life. The machine described in his thought experiment is often described as the "Experience Motorcar." The machine works by giving the participant connected to it the sensation of any experience they desired and is said to produce sensations that are indistinguishable from real life experiences.[67]

Nozick outlined the "utility monster" thought experiment as an attempted criticism to utilitarianism. Commonsensical ideals provides guidance for acting morally, but also to maximizing happiness. The utility monster is a hypothetical being that generates farthermost amount of theoretical pleasure units compared to the boilerplate person. Consider a situation such as the utility monster receiving fifty units of pleasure from eating a cake versus 40 other people receiving only i unit of pleasure per cake eaten. Although each private receives the same treatment or proficient, the utility monster somehow generates more than all the other people combined. Given many commonsensical commitments to maximizing utility related to pleasure, the idea experiment is meant to forcefulness utilitarians to commit themselves to feeding the utility monster instead of a mass of other people, despite our general intuitions insisting otherwise. The criticism essentially comes in the course of a reductio ad absurdum criticism by showing that utilitarians prefer a view that is cool to our moral intuitions, specifically that we should consider the utility monster with much more regard than a number of other people.[68]

Happiness enquiry [edit]

Happiness enquiry is the quantitative and theoretical study of happiness, positive and negative affect, well-being, quality of life, life satisfaction and related concepts. It is especially influenced past psychologists, but besides sociologists and economists accept contributed. The tracking of Gross National Happiness or the satisfaction of life abound increasingly pop as the economic science of happiness challenges traditional economical aims.[69]

Richard Layard has been very influential in this surface area. He has shown that mental affliction is the master crusade of unhappiness.[lxx] Other, more influential researchers are Ed Diener, Ruut Veenhoven and Daniel Kahneman.

Sonja Lyubomirsky [edit]

Sonja Lyubomirsky asserted in her 2007 book, The How of Happiness, that happiness is 50 percent genetically determined (based on twin studies),[71] 10 percent circumstantial, and 40 percent subject to self-control.[72]

Bear on of individualism [edit]

Hedonism appears to be more strongly related to happiness in more individualistic cultures.[73]

Happiness movement [edit]

Happiness is becoming a more conspicuously delineated aim in the West, both of individuals and politics (including happiness economics). The World Happiness Study shows the level of involvement, and organisations such as Action for Happiness undertake practical deportment.

Cultures not seeking to maximise happiness [edit]

Not all cultures seek to maximise happiness,[74] [75] [76] and some cultures are averse to happiness.[77] [78] Also June Gruber suggests that seeking happiness can accept negative furnishings, such equally failed over-high expectations,[79] and instead advocates a more open up stance to all emotions.[fourscore] Other inquiry has analyzed possible merchandise-offs between happiness and meaning in life.[81] [82] [83] Those not seeking to maximize happiness are in contrast to the moral theory of utilitarianism which states our ethical obligation is to maximize the cyberspace amount of happiness/pleasure in the world, because all moral agents with equal regard.[84]

See also [edit]

- Happiness

- Eudaimonia

- Religion and happiness

- Happiness in Judaism

- Self-fulfillment

- The good life

- Meaningful life

- Significant-making

- Logotherapy

- Positive psychology

- World Happiness Report

- The Happiness Hypothesis

Notes [edit]

- ^ Dante identified Boethius as the "last of the Romans and first of the Scholastics" among the doctors in his Paradise (see The Divine Comedy and also below).

References [edit]

- ^ Cassin et al. Dictionary of Untranslatables. Princeton Academy Press, 2014. Print.

- ^ Happiness. stanford.edu. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford Academy. 2011.

- ^ Sturt, Henry (1903). "Happiness". International Journal of Ideals. 13 (2): 207–221. doi:10.1086/intejethi.13.2.2376452. JSTOR 2376452. S2CID 222446622.

- ^ Democritus. stanford.edu. Metaphysics Inquiry Lab, Stanford University. 2016.

- ^ a b Plato, The Republic 10.612b

- ^ Joshua Olsen, Plato, Happiness and Justice. academia.edu.

- ^ Mohr, Richard D. (1987). "A Platonic Happiness". History of Philosophy Quarterly. 4 (ii): 131–145. JSTOR 27743804.

- ^ a b Dimmock, Marking; Fisher, Andrew (2017). "Aristotelian Virtue Ethics". Ethics for A-Level. pp. 49–63. ISBN978-1-78374-388-ix. JSTOR j.ctt1wc7r6j.7.

- ^ Daniel Due north. Robinson. (1999). Aristotle's Psychology. Published past Daniel Due north. Robinson. ISBN 0-9672066-0-X ISBN 978-0967206608

- ^ Aristotle., Bartlett, R. C., & Collins, S. D. (2011). Aristotle'south Nicomachean ideals. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- ^ Book I Chapter i 1094a.

- ^ Kraut, Richard, "Aristotle's Ethics", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2012 Edition), Edward North. Zalta (ed.), URL = <http://plato.stanford.edu/athenaeum/win2012/entries/aristotle-ethics/>

- ^ Xenophon, Symposium, iv. 41.

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius, Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers, vi. 3

- ^ Cynics – The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- ^ "The Stoic Sage". ancientworlds.cyberspace.

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius, Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers, two. 96–97

- ^ Diogenes the Cynics: Sayings and Anecdotes with Other Popular Moralists, trans. Robin Hard. Oxford Academy Printing, 2012. Page 152.

- ^ Annas, Julia (1995). The Morality of Happiness . Oxford University Press. p. 230. ISBN0-xix-509652-5.

- ^ Aelian, Historical Miscellany 14.6

- ^ Diogenes the Cynics: Sayings and Anecdotes with Other Popular Moralists, trans. Robin Hard. Oxford University Press, 2012. Page 124.

- ^ Copleston, Frederick Charles (2003). A History of Philosophy: Book i. Continuum International. p. 122. ISBN0-8264-6895-0.

- ^ Vincent Cook. "Epicurus – Principal Doctrines". epicurus.internet. Archived from the original on 7 April 2007. Retrieved 3 October 2015.

- ^ Hutchinson, D. S. (Introduction) (1994). The Epicurus Reader: Selected Writings and Testimonia. Cambridge: Hackett. p. vi.

- ^ Marcus Aurelius, Meditations. 3.12

- ^ Sharpe, Matthew. "Stoic Virtue Ethics." Handbook of Virtue Ethics, 2013, 28–41.

- ^ "Mod Stoicism | Build The Fire". Build The Fire. 9 February 2016. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^ Harper, Douglas (November 2001). "Online Etymology Dictionary – Stoic". Retrieved ii September 2006.

- ^ Stoicism, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ Russell, Bertrand. A History of Western Philosophy

- ^ Inwood, Brad (1986). "Goal and Target in Stoicism". The Journal of Philosophy. 83 (10): 547–556. doi:x.2307/2026429. JSTOR 2026429.

- ^ a b Paola, Omar Di (xiii June 2014). "Philosophical thought of the Schoolhouse of the Sextii – Di Paola – EPEKEINA. International Journal of Ontology. History and Critics". Ricercafilosofica.it. iv (1–2). doi:10.7408/epkn.v4i1-2.74.

- ^ Emily Wilson, The Greatest Empire: A Life of Seneca. Oxford Academy Printing, 2014. p.54-55

- ^ St. Augustine, Confessions. Trans, Henry Chadwick. Oxford University Press, 2008. p:3

- ^ St. Augustine, Confessions. Trans, Henry Chadwick. Oxford Academy Press, 2008. p:199

- ^ Mendelson, Michael (24 March 2000). Saint Augustine. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 21 Dec 2012.

- ^ https://world wide web.psychologytoday.com/blog/ideals-everyone/201106/achieving-hapGenesis cosmos narrativepiness-advice-augustine

- ^ a b c O'Connell, R. J. (1963). "The Enneads and St. Augustine'southward Prototype of Happiness". Vigiliae Christianae. 17 (3): 129–164. doi:10.2307/1582804. JSTOR 1582804.

- ^ "Achieving Happiness: Advice from Augustine". Psychology Today.

- ^ a b "True Happiness and The Consolation of Philosophy". catholic.com. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved iii Oct 2015.

- ^ Introduction to The Consolation of Philosophy, Oxford Earth'south Classics, 2000.

- ^ Sanderson Beck (1996).

- ^ "Avicenna (Persian philosopher and scientist) – Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved 7 January 2012.

- ^ Engebretson, Kath; de Souza, Marian; Durka, Gloria; Gearon, Liam (17 August 2010). International Handbook of Inter-religious Education. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 208. ISBN978-i-4020-9260-ii.

- ^ "Influence of Arabic and Islamic Philosophy on the Latin Due west". stanford.edu. Metaphysics Enquiry Lab, Stanford University. 2018.

- ^ "Ghazali, al-". The Columbia Encyclopedia . Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- ^ Böwering, Gerhard (1995). "Review of The Alchemy of Happiness, Abû Hâmid Muḥammad al-Ghazzâlî". Journal of Almost Eastern Studies. 54 (iii): 227–228. doi:10.1086/373761. JSTOR 546305.

- ^ Bodman, Herbert L. (1993). "Review of The Alchemy of Happiness". Periodical of Earth History. four (2): 336–338. JSTOR 20078571.

- ^ Imam Muhammad Al-Ghazali (1910). "The Alchemy of Happiness". Retrieved 8 January 2016.

This commodity incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain .

This commodity incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain . - ^ Maimonides: Abū ʿImrān Mūsā [Moses] ibn ʿUbayd Allāh [Maymūn] al-Qurṭubī [1]

- ^ A Biographical and Historiographical Critique of Moses Maimonides Archived 24 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Maimonides – Net Encyclopedia of Philosophy". utm.edu.

- ^ "Summa Theologica: Treatise on the Last Finish (QQ[ane]–5): Question. three – WHAT IS HAPPINESS (8 Articles)". sacred-texts.com.

- ^ Catholic Online. "St. Thomas Aquinas". catholic.org.

- ^ a b c d "Aquinas: Moral Philosophy – Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy". utm.edu.

- ^ "Summa Theologica". sacred-texts.com.

- ^ ST, I-Ii, Q. 2, art. 8.

- ^ "SparkNotes: Thomas Aquinas (c. 1225–1274): Summa Theologica: The Purpose of Man". sparknotes.com.

- ^ a b "Montaigne, Michel de – Net Encyclopedia of Philosophy". utm.edu.

- ^ a b "Bentham, Jeremy – Net Encyclopedia of Philosophy". utm.edu.

- ^ Arthur Schopenhauer, The Globe every bit Will and Idea. Cologne 1997, Volume One, §52th.

- ^ "Władysław Tatarkiewicz," Encyklopedia Polski, p. 686.

- ^ Herbert Marcuse. stanford.edu. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford Academy. 2017.

- ^ Marcuse, Herbert (1991). "Introduction to the 2nd Edition". 1-dimensional Human being: studies in ideology of advanced industrial society. London: Routledge. p. 3. ISBN978-0-415-07429-2.

- ^ a b Smith, Emily Esfahani (22 October 2014). "A Psychiatrist Who Survived The Holocaust Explains Why Meaningfulness Matters More Than Happiness". Business Insider. The Atlantic.

- ^ Feser, Edward (4 May 2005). "Nozick, Robert". Cyberspace Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ Crisp, Roger (2006). "Hedonism Reconsidered". Philosophy and Phenomenological Enquiry. 73 (three): 619–645. doi:10.2307/40041013. JSTOR 40041013.

- ^ Sridharan, Vishnu (2016). "Utility Monsters and the Distribution of Dharmas: A Respond to Charles Goodman". Philosophy East and West. 66 (two): 650–652. doi:10.1353/pew.2016.0033. JSTOR 43830917. S2CID 170234711.

- ^ Layard, Richard (1 March 2006). "Happiness and Public Policy: A Claiming to the Profession". The Economic Journal. 116 (510): C24–C33. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0297.2006.01073.x. JSTOR 3590410. S2CID 9780718.

- ^ Layard, Richard (7 April 2011). Happiness: Lessons from a New Science. Penguin. ASIN B004TRQAS6. [ page needed ]

- ^ Lyubomirsky, Sonja; Sheldon, Kennon M.; Schkade, David (ane June 2005). "Pursuing Happiness: The Architecture of Sustainable Alter". Review of General Psychology. 9 (2): 111–131. CiteSeerXten.ane.ane.335.9655. doi:x.1037/1089-2680.9.2.111. S2CID 6705969.

- ^ Halpern, Sue (3 April 2008). "Are You Happy?". The New York Review.

- ^ Joshanloo, Mohsen; Jarden, Aaron (i May 2016). "Individualism as the moderator of the relationship between hedonism and happiness: A report in 19 nations". Personality and Individual Differences. 94: 149–152. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2016.01.025.

- ^ Hornsey, Matthew J.; Bain, Paul Thou.; Harris, Emily A.; Lebedeva, Nadezhda; Kashima, Emiko S.; Guan, Yanjun; González, Roberto; Chen, Sylvia Xiaohua; Blumen, Sheyla (2018). "How Much is Enough in a Perfect World? Cultural Variation in Ideal Levels of Happiness, Pleasure, Liberty, Health, Self-Esteem, Longevity, and Intelligence" (PDF). Psychological Science (Submitted manuscript). 29 (ix): 1393–1404. doi:10.1177/0956797618768058. PMID 29889603. S2CID 48355171.

- ^ See the piece of work of Jeanne Tsai

- ^ Come across Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness#Meaning of "happiness" ref. the pregnant of the US Announcement of Independence phrase

- ^ Joshanloo, Mohsen; Weijers, Dan (1 June 2014). "Aversion to Happiness Beyond Cultures: A Review of Where and Why People are Averse to Happiness". Journal of Happiness Studies. fifteen (iii): 717–735. doi:10.1007/s10902-013-9489-9. S2CID 144425713.

- ^ "Study sheds low-cal on how cultures differ in their happiness beliefs".

- ^ "Positive Emotion and Psychopathology Lab - Director Dr. June Gruber".

- ^ Davis, Nicola; Jackson, Graihagh (20 July 2018). "The nighttime side of happiness – Science Weekly podcast". The Guardian.

- ^ Baumeister, Roy F.; Vohs, Kathleen D.; Aaker, Jennifer L.; Garbinsky, Emily N. (November 2013). "Some key differences between a happy life and a meaningful life". The Journal of Positive Psychology. viii (vi): 505–516. doi:10.1080/17439760.2013.830764. S2CID 11271686.

- ^ Abe, Jo Ann A. (2 September 2016). "A longitudinal follow-up report of happiness and pregnant-making". The Journal of Positive Psychology. xi (5): 489–498. doi:x.1080/17439760.2015.1117129. S2CID 147375212.

- ^ Kaufman, Scott Barry (30 January 2016). "The Differences between Happiness and Meaning in Life". Scientific American Blog Network.

- ^ Commuter, Julia (2014), Zalta, Edward Northward. (ed.), "The History of Utilitarianism", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Wintertime 2014 ed.), Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, retrieved twenty November 2021

Further reading [edit]

- 14th Dalai Lama, co-authored with Howard C. Cutler, The Art of Happiness, 2003.

- Jonathan Haidt, The Happiness Hypothesis: Finding Modern Truth in Ancient Wisdom, 2006.

External links [edit]

- Happiness, BBC Radio 4 discussion with Angie Hobbs, Simon Blackburn and Anthony Grayling (In Our Time, 24 January. 2002)

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philosophy_of_happiness

0 Response to "7 Happiness Sins a Life of Happiness and Fulfillment Review"

Post a Comment